On the 26 November 1979, South Korea’s President Park Chung-hee sat down to dinner with Kim Jae-gyu, the Director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency [KCIA]. After an argument, Kim pulled out a Beretta and shot the president. The pistol then jammed. Kim left the room and borrowed a Smith and Wesson. The wounded Park escaped to a bathroom. Kim followed him and after a brief conversation shot him in the head - execution style.

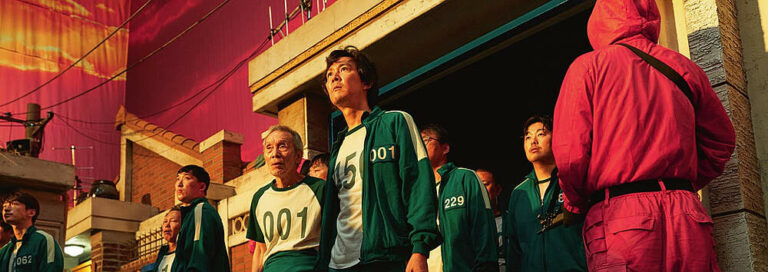

The scene of Park’s assassination would have been familiar to anybody who has watched Netflix’s South Korean TV drama series, The Squid Game. A global phenomenon, it has become the world’s most watched drama series recording some 142m hours viewing versus 82m hours for second place Bridgerton; over the course of nine episodes of The Squid Game, 456 players compete in a dystopian survival drama in which the winner of a series of deadly children’s games bags a $45m jackpot. The 455 losers are mainly killed by graphically realistic pistol shots to the head.

Violent death is one of the main themes of modern Korean history. In 1895 when Korean vassalage was resisted by Empress Myung-Sung (aka Queen Min), Japan’s consul organised a group of sword-wielding Japanese samurai to assassinate her. In the early hours of 8 October Queen Min was dragged out of her royal residence and hacked to death.

Korea continued to be the butt of Japan’s imperial advance in the 20th Century. After the Russo-Japanese war mediator President Theodore Roosevelt fudged the Korean issue by guaranteeing its freedom while at the same time recognising Japan’s ‘paramount political, military and economic interests in Korea.’ Subsequently Japan murdered Korea’s prime minister after he was lured out of a cabinet meeting and forced its government to accept a Japanese protectorate. Then, when appeal was made to America for help, the Japanese slaughtered 50,000 mainly Christian, pro-Western Koreans.

This was just the beginning of Korea’s 20th Century miseries. During the Pacific War, over a million Korean men were forced to work as slave labourers while 200,000 Korean women were coerced into prostitution to service Emperor Hirohito’s armies – sometimes as many as 100 soldiers per day. Korean dissidents suffered vivisection and biological experimentation in Japan’s R&D concentration camp, Unit 731, near Harbin in Manchuria.

Worse was to come. After the Pacific War, the north’s socialist dictator, Kim Il-sung persuaded Russia to back his invasion of the American occupied south. In the resulting Korean War 2.5 million Koreans died, about ten percent of its population.

The state of war with North Korea has continued ever since. Five years before President Park’s murder, his wife was assassinated by a North Korean gunman. Then in 1983 North Korean assassins killed most of South Korea’s cabinet in a Rangoon bomb attack; President Chun survived because his cortege was late.

South Koreans live in constant fear of attack from the north whose border is just 23km Seoul.

It is revealing that The Squid Game’s most popular sub-plot follows a North Korean escapee who wants to buy her mother’s freedom. Korea’s ocietal paranoia has only heightened since North Korea exploded its first atom bomb in 2006. For large parts of its early history South Korea has lived under military curfew.

Life in South Korea has an edge. Koreans like Israelis, another people under perpetual threat of annihilation, are famously combative. In Korea, office disputes often end in fist fights. Like Israel, South Korea has achieved a remarkable post-war economic miracle. For Koreans economic growth is survival.

Furthermore, sacrifice, a theme that runs through The Squid Game, is an important part of Korean culture. In the Second Oil Crisis companies saved electricity by removing every other lightbulb and shutting office elevators; the stairways were filled with uncomplaining staff endlessly walking up and down twenty or thirty floors or more - another scene frequently reprised in The Squid Game.

It seems clear that the brutality of modern Korean history is the overwhelming psychological background to The Squid Game; fear, violence and repression are locked into the DNA of the Korean People. Netflix’s record break show may be a fictional survival-drama, but for South Koreans survival is a perpetual real-life experience.